What Code Review Research Gets Wrong About Real Development Teams

Table Of Links

1 INTRODUCTION

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED WORK

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

4 MAPPING STUDY RESULTS

5 SURVEY RESULTS

6 COMPARING THE STATE-OF-THE-ART AND THE PRACTITIONERS’ PERCEPTIONS

7 DISCUSSION

8 CONCLUSIONS AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

REFERENCES

\

7 DISCUSSION

In this section, we summarize the research directions that emerged from analyzing the state-of-art and the practitioner survey. Furthermore, we illustrate that our findings align with the observations made by Davila and Nunes [18], strengthening our common conclusions since our respective reviews cover a non-overlapping set of primary studies. Finally, we discuss the threats to validity associated with our research.

\

7.1 MCR research directions

We propose future MCR research directions based on current trends and our reflections, both obtained through our mapping study and survey with practitioners. We anchor this discussion in the MCR process steps shown in Figure 1 6 . Next, we propose relevant research topics, along with research questions that still remain to be answered.

\ 7.1.1 Preparation for code review.

Understanding code to be reviewed - Understanding the code was perceived as important by the survey respondents (c.f. Figure 7e). The solutions reported in the primary studies focus on a subset of patch characteristics that affect review readiness (such as [94, 118, 260]). However, is it possible to combine all patch characteristics into an overall score that can inform the submitter so they can improve the patch before sending it out for review? Review goal - After understanding the code to be reviewed, the next step is to decide the review goal. The survey respondents are positive about investigating the impact of code review on code quality in general and, more specifically, security (c.f., Figure 7a).

\ Our primary studies findings indicate that most issues found in code reviews are related to a subset of code quality attributes such as evolvability [68, 171]. Does that imply that only certain quality attributes can or should be evaluated with code reviews? Review scope - Another aspect of preparing for code review is to decide which artifacts to review, i.e., the review scope. Test code is seldom reviewed and is not considered worthy of review [224, 226]. However, the survey respondents consider test code review one of the most important research topics (c.f., Figure 7c).

\ In addition to test and production code, the popularity of third-party libraries (3pps) in software development is increasing, which leads to an important area of 3pp review. How to use risk-based assessment to scope the review target and the review goals to achieve an acceptable trade-off between effort and benefits? Optimizing review order - Factors influencing the review order in open source (OSS) projects can differ from proprietary projects or may have different importance.

\ For example, as mentioned in our primary studies [53, 105, 213], acceptance probability is one of the determinants in ordering OSS reviews (important to attract contributors). However, in proprietary projects, other determinants such as merge conflict probability may have more importance in determining the review order.

7.1.2 Reviewer selection.

Appropriate reviewer selection - The primary studies focus on identifying "good reviewers" based on certain predictors such as pull request content similarity [145, 211, 268, 275]. However, how much do "good reviewers" differ in review performance from "bad reviewers"? Number of reviewers - The primary studies establish a correlation between the number of reviewers and the review performance [95, 155, 174]. However, what are the factors determining the optimal number of reviewers?

7.1.3 Code checking.

After the preparation and reviewer selection step, the reviewers are notified and the actual review takes place. It is valuable to monitor the review process to learn new insights that can be codified in guidelines. It is known that code review can identify design issues [120, 178, 184, 189]. How can this identification be used as an input to create or update design guidelines? In addition, the primary studies found that good reviewers exhibit different code scanning patterns than less good reviewers [67, 83, 216, 252]. Such findings should be used to propose/ develop solutions that harvest this expertise from reviewers.

7.1.4 Reviewer interaction.

Review comment usefulness - Studies have investigated reviewer interaction through review comments. According to the primary studies, the usefulness of comments is determined by the changes caused by them [192, 205]. For example, a useless comment can be an inquiry about the code that leads to no change. However, such discussions can lead to knowledge sharing. Therefore, the semantics of comments should also be considered when determining their usefulness. Knowledge sharing - Experienced reviewers possess tacit knowledge that is difficult to formalize and convey to novice programmers.

\ Systems that could mine this knowledge from reviews would be an interesting avenue for research. It could be good if reviewers get a good mix of familiar and unknown code reviews to expand their expertise over time. Existing studies [90, 154, 155, 174, 208, 240] show that the expertise of reviewers is codified in reviews, but making that expertise tangible and accessible is still an open question. In addition, a review comment can sometimes contain links that provide additional information that could contribute to knowledge sharing.

\ Human aspects - When discussing reviewer interactions, human aspects received much attention in the reviewed primary studies. However, the investigation of review dynamics, social interactions, and review performance is focused on OSS projects. It is not known if such interactions differ in proprietary projects.

7.1.5 Review decision.

We have identified studies that automate code reviews. When static code analysis tools are used for automation, the rules are visible and explicit (white box). In contrast, the decision rules are not easily interpretable when using deep learning approaches (black box).

7.1.6 Overall code review process.

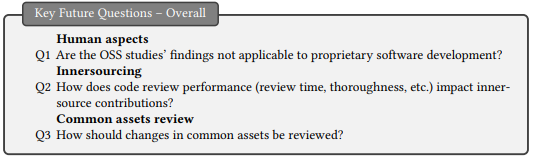

The future research directions and research questions that could not be directly mapped to any specific step in the code review process are categorized as overall topics. Human aspects - The difference between core and irregular reviewers has been studied mostly in the context of open source (OSS) [65, 73, 75, 150, 199]. In our survey, the respondents perceived the difference between core and irregular reviewers as unimportant. However, the survey respondents were mostly from companies working with proprietary projects. It would be interesting to investigate if human factors matter more in OSS than in proprietary software development.

\ The survey respondents considered the research on human aspects not as relevant as the research on other themes. We pose that, since most of the research on organizations and human factors is performed in OSS projects, research on human aspects in companies mainly working with proprietary projects is still very relevant as the human factors might differ between OSS and proprietary contexts. Innersourcing - We have seen MCR research in OSS and in commercial projects. However, we do know very little about MCR in Innersourcing. Similar to the open source way of working, Innersourcing promotes contributions across different projects within an organization.

\ A delay or incomplete review may discourage an Innersource contributor. Human factors may be more relevant for commercial projects in the context of Innersourcing. Code reuse - Common assets are code that is reused within an organization. It would be interesting to investigate how changes made to common assets should be reviewed. For example, should reviewers from teams that use the common assets be invited to review new changes?

7.2 A comparison with other reviews and surveys

Figure 11 illustrates the overlap and differences between the primary studies identified in this paper and the works by Wang et al., and Davila and Nunes. Interestingly, even though the search period and aims of the three studies are comparable in scope, the included primary studies are quite diverse. Wohlin et al. [40] have made similar observations when comparing the results of two comparable mapping studies. While a detailed analysis, as done by Wohlin et al., is out of the scope of this paper, we speculate that the main reason for the divergence of primary studies is the emphasis on different keywords in the respective searches.

\ While Wang et al., and Davila and Nunes included "inspection" in their search string, we explicitly did not. The term is associated with traditional code inspections, which is a different process than MCR, as explained in Section 2.2. Rather, we included terms that are associated with MCR, like "pull request" and "patch acceptance". Wang et al. excluded also papers that were not published in a high impact venue, likely leading to the lower number of included primary studies. We also explicitly did not exclude any papers based on their quality. Instead, we provide an assessment of the studies’ rigor and relevance [23]. As described in Section 4.1, there is a lack of involvement of human subjects in code review research.

\ As code review is a human-centric process, researchers should involve more human subjects to evaluate the feasibility of code review interventions. This research gap has also been observed by Davila and Nunes’ review [18], who called for more user studies on MCR. Moreover, researchers should consider more data sources in addition to analyzing repositories to achieve triangulation, strengthening the conclusions that can be drawn on the developed interventions.

\ This is analogous to the observation by Davila and Nunes [18], who found that a majority of MCR research focuses on particular open source projects (Qt, Openstack, and Android) or is conducted in large companies such as Microsoft and Google. MCR practices and motivations in companies working primarily with proprietary projects may be different than in open source projects. In companies, the contributions and reviews are not voluntary work; furthermore, it is more likely that the reviewers and contributors known each other. Moreover, there may be domain or organizationspecific requirements that may not be present in open source projects.

\ Therefore, there is a need to investigate more MCR in the context of proprietary software projects. It is also worth mentioning that there is a lack of studies in small and medium-sized companies. Such new studies could shed light on the question if the knowledge accumulated through MCR is also present in small and medium companies’ projects [18]. The surveyed practitioners were most positive about the impact of code reviews on product quality and human aspects (IOF) and modern code review process properties (CRP). Therefore, given the relatively low number of studies in these themes, we suggest conducting more research investigating how MCR affects and is affected.

\ Davila and Nunes [18] share a similar insight, calling for more research on MCR process improvement. Previous studies that surveyed practitioners and analyzed the impact of software engineering research [13, 27] could not establish any correlation (positive or negative) between research impact and practitioner interest. These observations are to a large extent in line with our results (Section 6.2). There is only one statistical significant correlation between the Support Systems theme and research impact, indicating that statements containing publications with high citation count were considered as important to investigate (and vice-versa).

\ In Section 2.4, we report also that the past surveys on practitioner perception found that 67-71% of the research was seen positively. Looking at the results in Figure 7, we observe that 24 statements have more negative than positive ratings and 22 statements have more positive than negative ratings (48% positive). This is considerably lower than in the previous surveys. However, it could be attributed to the difference in the administered survey instruments. In our survey, the participants had to distribute negative, neutral, and positive perception according to a predefined distribution, i.e., they could not find all research negative or positive.

7.3 Validity threats

Our philosophical worldview is pragmatic, which is often adopted by software engineering researchers [31]. We use therefore a mixed-method approach (systematic mapping study and survey) to answer our research questions. The commonly used categorizations to analyze and report validity threats, such as internal, external, conclusion and construct validity of the post-positivist worldview (such as Wohlin et al [39]), are adequate for quantitative research. However, they either do not capture all relevant threats for qualitative research, or are formulated in a way that is not compatible with an interpretative worldview.

\ The same argument can be made for threat categorizations originating from the interpretative worldview (such as Runeson et al. [33]). Petersen and Gencel [31] have therefore proposed a complementary validity threat categorization, based on work by Maxwell [29], that is adequate for a pragmatic worldview. We structure the remainder of the section according to their categorization and discuss validity threats w.r.t. each research method. Please note that repeatability (reproducibility/dependability) of this research is a function of all the threat categories together [31], and therefore not discussed individually.

\ 7.3.1 Descriptive validity. Threats in this category concern the factual accuracy of the made observations [31]. We have designed and used a data extraction form to collect the information from the reviewed studies. We copied contribution statements that can be traced back to the original studies. Furthermore, we have piloted the survey instrument with three practitioners to identify functional defects and usability issues. Extraction form, survey instrument and collected data are available in an online repository [6].

\ 7.3.2 Theoretical validity. Threats in this category concern the ability to capture practically the intended theoretical concepts, which includes the control of confounding factors and biases [31].

\ Study identification. During the search we could have missed papers that could have been relevant but were not identified by the search string. We addressed this threat with a careful selection of keywords and not limiting the scope of the search to a particular population, comparison or outcome (PICO criteria [24]). For the intervention criterion, we used variants of terms that we deemed relevant and associated with modern code reviews.

\ Due to this association, we did not choose keywords for the population criterion (e.g. "software engineering") as they could have potentially reduced the number of relevant search hits. We have compared our primary studies with the set of other systematic literature studies (see Figure 11). We have identified 136 studies that the other reviews missed, while not identifying 69 studies that were found by the other reviews. Hence, there is a moderate threat that we missed relevant studies.

\ Study selection. Researcher bias could have led to the wrongful exclusion of relevant papers. We addressed this threat by including all three authors in the selection process who reviewed an independent set of studies. To align our selection criteria, we established objective inclusion and exclusion criteria, which we piloted and refined when we found divergences in our selection (see Selection in Section 3.1). Furthermore, we adopted an inclusive selection process, postponing the decision on exclusion for unsure papers to the data extraction step, when it would be clear that the study did not contain the information we required to answer our research questions. When we excluded a paper, we documented the decision with the particular exclusion criterion.

\ Data extraction. Researcher bias could have led to a incorrect extraction of data. All three authors were involved in the data extraction as well. We also conducted two pilot extractions to gain a common interpretation of the extraction items. We revised the description of rigor and relevance criteria based on the pilot process. After the pilot process we continued to extract data from primary studies with an overlap of 20% where we achieved high consensus.

\ Statement order. All survey participants received the statements in the same order. The participants may have tended to agree more to statements listed at the beginning than at the end of the survey. Our survey instrument was designed in such a way that the participants could change their rating anytime, i.e. also when they have seen all statements. Looking at our results, the themes that were judged early in the survey (IOF) seem to have received more agreement than later themes (SS). However, participants have provided a consistent rating for the human factor related statements, independently of whether or not they appear in early or late positions in the survey. Therefore we assess the likelihood of this risk as low.

\ 7.3.3 Internal generalizability. Threats in this category concern the degree to which inferences from the collected data (quantitative or qualitative) are reasonable [31].

Statement ranking and factor analysis. We followed the recommendations for conducting the Q-Methodology [41], including factor analysis and interpretation. In addition, we report in detail how we interpret the quantitative results of the survey, providing a chain of evidence for our argumentation and conclusions.

\ Research amount and impact, and practitioners perceptions. There is a risk that practitioners understood that they need to judge if the topic in a statement affects them, rather than whether or not research on the topic is important. We counteracted this threat by designing the survey instrument in a way that reminds the respondents what the purpose of the ranking of statements is. Furthermore, the free-text answers in the survey provide a good indication that the respondents correctly understood the ranking task.

\ Identification of research roadmap. We have based our analysis on the contributions reported by the original authors of the studies. In contrast, the gaps we highlighted are based on what has not been reported (i.e. researched). As such, the proposed research agenda contain speculation on what might be fruitful to research. However, we do provide argumentation and references to the original studies, allowing readers to follow our reasoning.

\ 7.3.4 External generalizability. Threats in this category concern the degree to which inferences from the collected data (quantitative or qualitative) can be extended to the population from which the sample was drawn.

Definition of statements. There is a risk that the statements were formulated either too generic or too specific, not reflecting all aspects of the research studies they represent. The statements were defined based on the primary studies collected in the 2018 SMS. We then extended the SMS to include papers published until 2021, classifying all new studies, except one, under the existing statements, which indicates that the initially defined statements were still useful after four years of research. It is however likely that with the advancement of MCR practice, new research emerges that requires also an update of the statements if they survey is replicated in the future.

\ Survey sample. As discussed in Section 2.2, the main difference between proprietary and open source software development, in relation to MCR, is the purpose of the MCR practice. The respondents of our survey mainly work in companies that primarily work in proprietary projects. In this context, the main purpose of MCR is knowledge dissemination rather than building relationships to core developers [76]. Indeed, we observe in our survey results that research aspects of human factors in relation to MCR are perceived as less important (see Section 5.2). However, the factor analysis in Section 5.3 provides a more differentiated view, based on the profile of the survey respondents. For example, senior roles are more favourable towards human factors research in MCR than respondents with less professional experience. Nevertheless, future work could replicate the survey in open source communities, allowing a differential analysis.

\ Identification of research roadmap. While the inferences we draw from the reviewed studies may be sound within the sample we studied, there is a moderate threat that the future research we propose has already been conducted in the studies we did not review (see discussion on study identification in Section 7.3.2).

\ 7.3.5 Interpretive validity. Threats in this category concern the validity of the conclusions that are drawn by the researchers by interpreting the data [31].

\ Definition of themes. Researcher bias could have lead to an inaccurate classification of the studies in the SMS. We divided the primary studies for analysis among the authors. Each paper that was analysed by one author was reviewed by the two other authors, and disagreements were discussed until a change in the classification was made or consensus was reached.

\ Definition of statements. Also the formulation of statements representing a study, used in the survey, could have been affected by researcher bias. To address this treat, we followed an iterative process in which we revised the statements and the association of papers to these statements. All three authors were involved in this process and reviewed each others formulations and classifications to check for consistency as well as allow for different perspectives on the material.

\ There are two statements where more than one aspect is introduced: in the HOF theme, "age and experience" and "performance and quality" in the SS theme. A respondent may have an opinion on just one of the aspects and therefore misrepresent the rating of the other aspect. We asked the practitioners to provide explanations for extreme ratings i.e., -3 and +3 which makes it possible to know which aspects the practitioners focused on. However, such explanations are not available for ratings other than -3 to +3. Since only two out of 46 statements are affected we judge the risk of misrepresentation as low.

\ Identification of research roadmap. Finally, the identification of gaps in the MCR research corpus could have been affected by researcher bias. The first and second author conducted a workshop in which they independently read the MCR contributions in Section 4.2. Then, they discussed their ideas of what questions have not been answered by the reviewed research and which questions would be interesting to find an answer for, especially if there is some support from the survey results that a particular statement was perceived important to investigate by the practitioners. This initial formulation of research gaps was reviewed by the third author.

:::info Authors:

- DEEPIKA BADAMPUDI

- MICHAEL UNTERKALMSTEINER

- RICARDO BRITTO

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

:::

\

You May Also Like

U.S. Moves Grip on Crypto Regulation Intensifies

Wie verkoopt er nu Bitcoin? Volgens deze analyse gaat het vooral om nieuwe beleggers